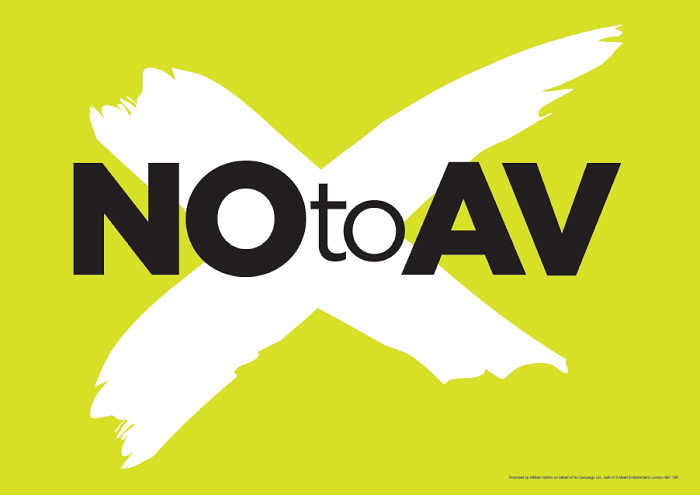

| Britain says ‘no’ to AV: reflections on the result |

|

|

| Monday, 09 May 2011 09:06 |

|

Britain has clearly said ‘no’ to AV in a nationwide referendum that saw two thirds of voters opting against electoral reform. Rima Saini reflects on the campaign battle fought within the coalition and shares her views on the results of this historical referendum with The Samosa.

So, the count came in, and of the 42 per cent of the population that cast their vote at the AV referendum on Thursday, 69 per cent shot it down with a resounding and unequivocal 'no'. A victory for the anti-reformists or a relief? Judging by the nature of the campaign, the result was by most people's expectations the culmination of a hasty coalition compromise, enough to disenchant this optimist's expectations for a useful discussion on electoral reform.

The campaign itself wasn't exciting, by any means. After an exhilarating discussion on global terrorism, human rights law and military intervention on Thursday night's BBC Question Time debate, AV did not seem to elicit the same idealistic political fervour amongst the audience members. There have been no crowds in the street, no voters poised on the edge of their seat as the results came in, despite some nifty graphics and green-screening by the BBC News team. Indeed many, in great British political tradition, just did not bother to vote, the irony here being evident: voter apathy rearing its sleepy head once again, casting its indifferent glance over British democracy at what was potentially a crucial juncture in its political development.

The most intriguing aspect of the past few months has had to be the political alliances and scathing enmities that were forged across the Yes/No divide, not forgetting the ludicrous and admittedly puzzling propaganda, some of which seemed to equate a vote for reform as a vote against maternity units for premature babies. We were harshly reminded of the ideological gap between the two parties of our current coalition by their starkly contrasting perspectives on the issue, doing little to bolster any confidence we had in them of steering us safely through the economic recession.

The smears, lies and spurious claims exuding from the 'yes' and 'no' camps merely reinforced the ideas that the referendum was largely a vehicle for inter-party scuffles, used as a marketing strategy (by both sides of the political spectrum) to de-legitimatise their respective political adversaries. David Cameron may have been right, with the help of some impressive alliteration, that the talk of 'proportionality and preferences, probabilities and possibilities' led to a dizzying and confusing debate. But his 'gut instinct', the apparent source of his conviction that AV is wrong, probably bore from his exasperation at having to indulge, even if only temporarily, the reformist agenda of his coalition partners. It is not easy, therefore, to swallow without cynicism the declarations of a man who owes his position to the system as it is. I only hope the Liberal Democrats try and retain a clear and distinctive voice for change in the coalition (as per their post-referendum pledge) as their descent from the crest of the political wave intensifies.

One of the most contested claims made in the campaign was by Conservative Party chairman Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, who declared that AV entails pandering to extremists such as the BNP who, through voters’ second preferences, could potentially garner more than their fair share of political legitimacy. Others such as Labour MP David Lammy argued in response that they would never garner the majority required under AV to win seats given the radical nature of their message. The Guardian settled the debate by drawing on research undertaken by the IPPR, concluding that the party would simply not have the breadth of support it needs to swing any seats with secondary votes whereas currently, in a divided race, they could actually be afforded a much better chance. The BNP subsequently chimed in with their rejection of AV, but only in favour of proportional representation, which despite all its virtues as the system that could arguably prove most reflective and sensitive of the political landscape, would give them the opportunity to gain seats based on the proportion of votes they secure. For all their faults, therefore, we certainly cannot blame them of jumping on anyone's bandwagon in this instance.

This scaremongering elicited by the Conservatives was coupled by their standard appeal to the vague notion of 'Britishness' that is somehow reflected in the 'one person, one vote' ethos of first-past-the-post. They seem to be in agreement that democracy alone cannot rouse the disillusioned portions of the electorate, but some stirring nationalistic rhetoric can only help things along. We can try to accepting with all democratic humility, therefore, that the public have expressed their confidence in this system; the referendum question in all its simplicity gave us a decisive answer. This does not imply, however, that the chapter on voting reform must well and truly close and as I expressed in my pre-referendum article, it is not an issue that should be put to bed. No one could have predicted with any certainty how AV would have changed the British political landscape. But until we can engage in an informed debate set apart from the evocative arguments made by politicians to suit their political agendas, the issue of electoral reform has yet to receive the justice it deserves. |

| Last Updated on Monday, 09 May 2011 10:08 |

By Rima Saini

By Rima Saini